When the Bow River is the Low River

Joe Fowler

Watershed Stewardship Coordinator

Bow River Basin Council

When the cool air begins to signal fall’s arrival, or when the winter months seem endless, warm days feel like a blessing. When you can be outside in nothing more than a light sweater, it’s hard not to exclaim “What a beautiful day!” However, as someone who spends an abnormal amount of time thinking about river health, I often wonder what these “beautiful days” mean for water quantity and quality.

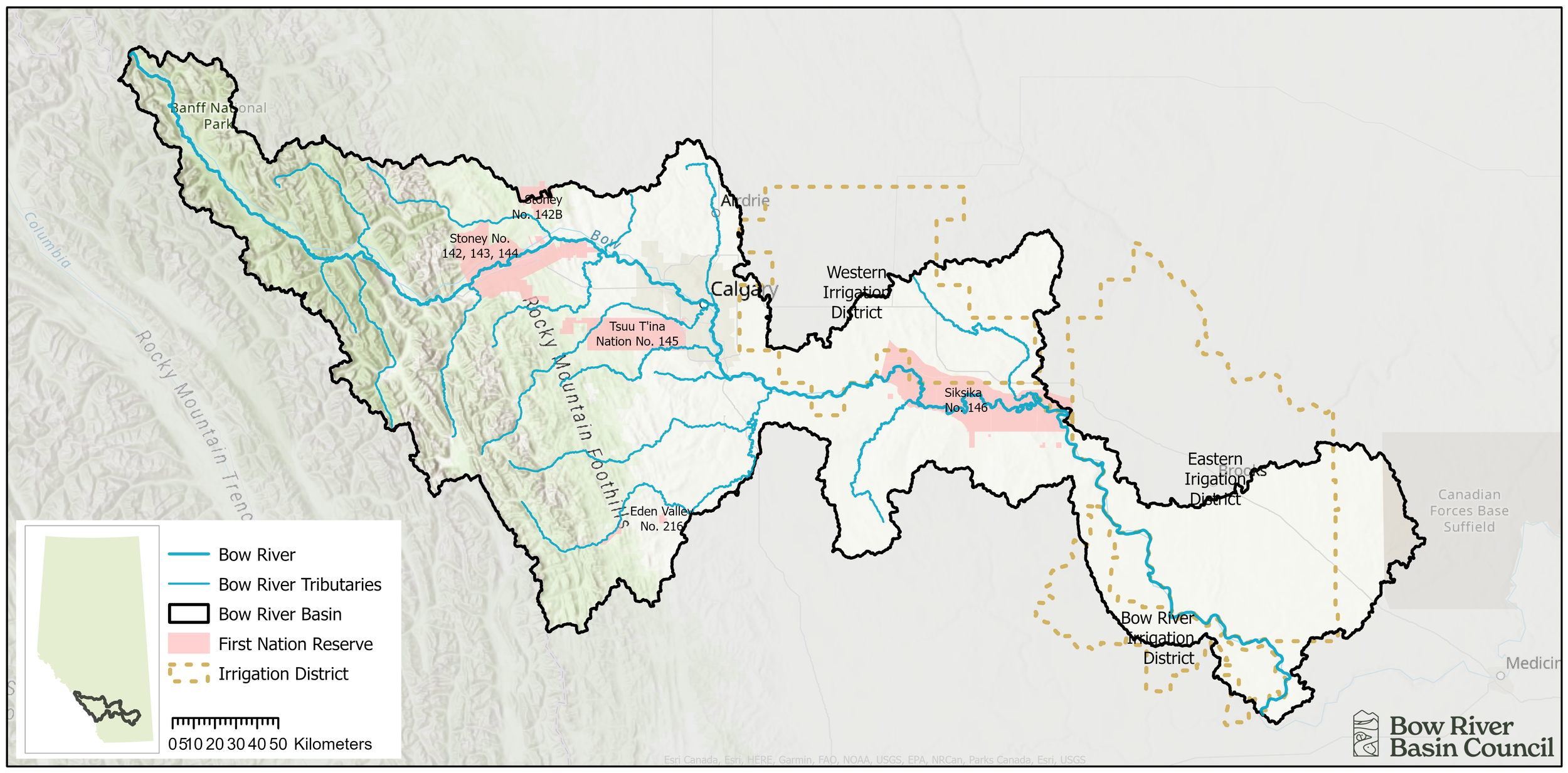

The City of Calgary, the Tsuut'ina Nation, Mînî Thnî, and Canmore are very close to the headwaters of the Bow River in Banff National Park.

Where does the water come from?

Mountains: Many communities within the Bow River Basin are situated within the mountain headwaters of the river - where it begins. The same mountains we admire and explore are the primary source of river water in the Bow River Basin. By the time it reaches Calgary, approximately 90% of our river flow comes from the mountain region (above Seebe in the Bow, or above Bragg Creek in the Elbow).

Mountains are our water towers, storing groundwater in their many cracks (and some caverns) from rain and snowmelt. In winter they cradle snow and ice which is slowly released during annual melt, mostly between May and August. Our iconic glaciers melt mostly in the late summer after snow is gone and provide Calgarians with a small (and decreasing) percentage of the overall yearly flow (1-3%), but in August, when there is less precipitation and more melt, glaciers may contribute as much 8-20% of the Bow River’s flow.

Precipitation: on average, more water falls on the mountain landscape as rain than as snow. After it rains or snow melts, the water infiltrates into the groundwater zone and ‘pushes’ older groundwater into the river. Thus, a large portion of water reaches the river as groundwater, which has been stored for varying periods (days to millennia).

Graphs courtesy of Caryn Sidharta, using the average Canadian snow/snow water equivalent of 13:1

Groundwater: an understated component of river flow. In the winter, almost all of the river flow is supplied by groundwater. In the summer, cold groundwater keeps the river cool. Since warm water holds less dissolved oxygen, the cool groundwater is important for aquatic wildlife. Native species, like Bull Trout and Westslope Cutthroat Trout have adapted to, and rely on, cold mountain water.

In the spring, when we see increased precipitation and snow melt, there is groundwater recharge in the alluvial aquifer, causing the water table to rise. The alluvial aquifer is the area of gravel and sand that is adjacent to, and exchanges water with the river along its path. It’s a lot of fun to say, but it’s difficult to casually drop in conversation. (Shall we go for a walk on the alluvial aquifer?)

Image courtesy of the Elbow River Watershed Partnership (erwp.org)

In the dry summer periods, groundwater continues to recharge the river. It slowly drains to the lower points in the landscape, which is where streams and rivers occur.

Managing through water shortages

Alberta Environment and Protected Areas is the Ministry responsible for managing water resources under the Water Act. There are 5 stages for managing water in times of shortage. The first begins with monitoring and close observation. As the situation becomes more serious, the government may continue to move through the different stages. We are currently at Stage 4, meaning multiple areas across Alberta have been affected, impacting water licensees, agricultural users, and household users. Unless we receive significant precipitation in the coming months, we should expect the province to move into Stage 5 – Declaring a State of Emergency in 2024. This decision is made when the low flows result in a significant risk to human health and safety. What will happen in a Stage 5? It is difficult to say, as a Stage 5 Water Emergency has never been declared in Alberta. However, Albertans have experienced multi-year droughts before in the 1930s, 1980s, and the early 2000s. I feel optimistic that we will get through this period, as Albertans we are collaborative and innovative – two traits that will come in handy this year!

Looking ahead

It’s hard to predict when a drought will end. To achieve “normal” water levels, we would need above average precipitation. We won’t know how the precipitation has impacted the river’s flow until later in the spring. The 2013 flood followed a drought season, so we have experienced a sudden shift before. However, many are already planning for another warm year and are wondering what they can do to help conserve water. Here are some actions you may want to consider at home.

Taking shorter showers and fewer baths is easy

This may be a good time to fix those leaky faucets and toilets

I have a feeling I will be embracing my brown lawn this summer

Investigate which native plants are the most drought-tolerant

After years of thinking about it, I will FINALLY get a rain barrel

Stay informed!

Download the Alberta Rivers App

Learn how to use it with this instructional video

Check out our website for upcoming drought workshops, events, and up-to-date information

These actions may seem small, but when combined with the cumulative impact of the community they can result in positive change. And on the days when we are blessed with rain or snow, it will be hard not to exclaim “what a beautiful day!”

Sending a massive THANK YOU to Caryn Sidharta and Cathy Ryan from the University of Calgary for carefully detailing the complexity and significance of precipitation, groundwater, and mountains to the Bow River.